17-22 Nov

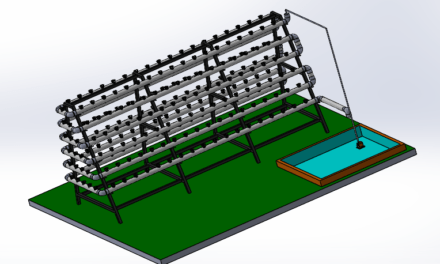

This week was largely dedicated to defining the core intention behind our BSF environmental black box project. We began by understanding the purpose and objective of building a chamber that can reliably maintain the ideal conditions needed for Black Soldier Fly larvae. The discussions helped us shape a clear picture of how temperature, humidity, and airflow interact in a controlled 1 m³ environment, and how these factors directly affect BSF growth efficiency.

A major part of the week revolved around exploring multiple ways to achieve the environmental stability we needed. We evaluated different heating and humidification concepts, debated their pros and cons, and mapped out several possible engineering routes. The goal was not to finalize the hardware yet, but to understand the system deeply enough to choose the most efficient and reliable approach later.

Key Discussions This Week

We spent most of the week discussing the objective, purpose, and engineering requirements that would define the system:

- Why the chamber is needed

- What environmental parameters must be controlled

- Hardware approaches to achieve stable heat + humidity

- How BSF biology interacts with environmental control

We explored multiple pathways for building this system:

- Steam-based heating + humidification

- Resistive heating + ultrasonic humidification

- Fan Pad system

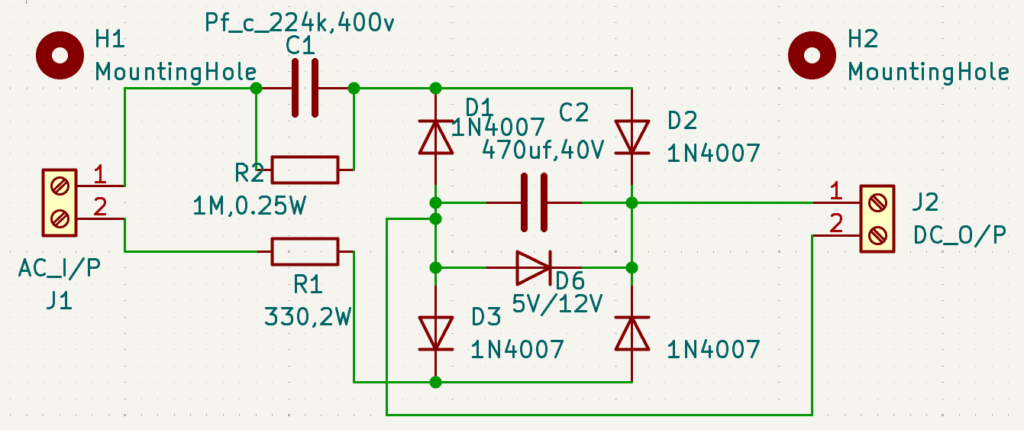

Alongside these discussions, I also worked on an AC-to-DC converter using a bridge rectifier. This small side task is an important building block for the larger system, as it will support the power needs of sensors, controllers, and possibly auxiliary components within the chamber.

24-29 Nov

Calculations, Thermodynamics, and Component Selection

Week 2 marked a shift from conceptual thinking to concrete engineering calculations. The entire thermodynamic profile of the chamber was analyzed—how much heat is required, how the chamber air behaves, how water contributes to humidity and thermal load, and how airflow affects the environment. This analytical phase was essential to determine the exact specifications of the components we will need.

All critical thermodynamic calculations were performed to determine:

- Energy needed to heat the entire chamber

- Heat absorbed by air

- Heat absorbed by water

- Energy required for evaporation

- Required airflow (CFM)

- Fan sizing

- Heater capacity

- Worst-case operating conditions

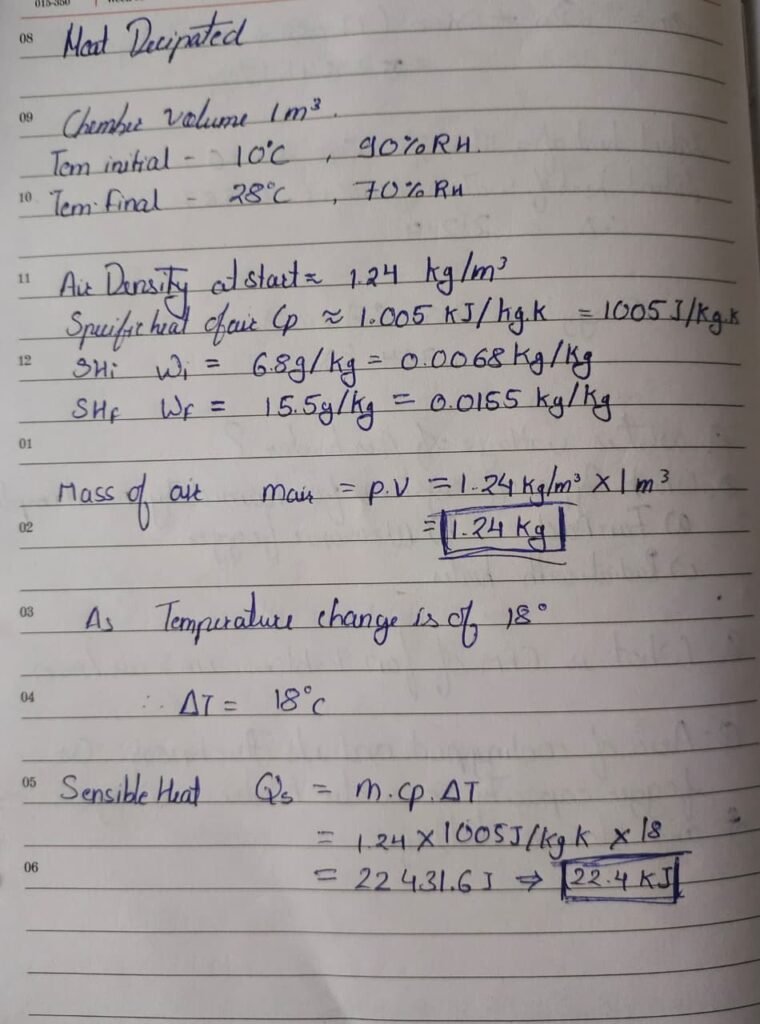

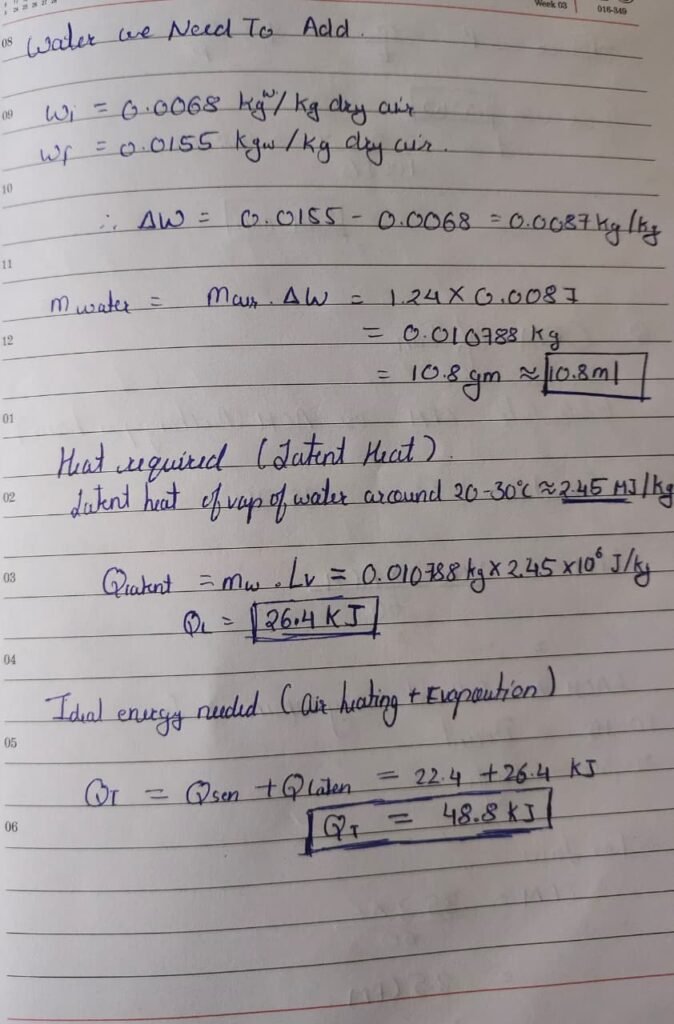

To design the system realistically, we assumed the worst-case starting condition: the chamber beginning at 10°C and needing to reach a stable 27–30°C with around 70% relative humidity. Using thermodynamic formulas, especially Q = m × Cp × ΔT, we calculated the energy required to raise the temperature of the 1 m³ air volume. Additional calculations were done for water heating and evaporation, since humidity control is just as important as heat for BSF larvae.

Key Thermodynamic Outcomes

- Heat required to warm chamber air: ~21.4 kJ

- Heat required to heat and evaporate water: ~17.44 kJ

- Total thermal energy needed: 38.84 kJ

These numbers include both sensible heating and latent heat required for water evaporation, ensuring that both temperature and humidity targets could be reached simultaneously. All calculations were validated using standard thermodynamic values such as air density, specific heat capacities, and latent heat of vaporization.

Component selection is done based on calculations and considering various factors

1.Water Heater (Boiling-based humidification + heating)

We selected a small water heater capable of boiling water to generate hot steam.

This solves two problems at once:

- Raises humidity naturally

- Adds heat to the chamber efficiently

This approach is simpler and more controllable compared to ultrasonic humidifiers in humid environments.

2. Resistive Air Heater

A resistive-type heating element will maintain a stable temperature between 27–30°C, compensating for:

- Heat loss to the environment

- Variations in larval activity

- External temperature fluctuations

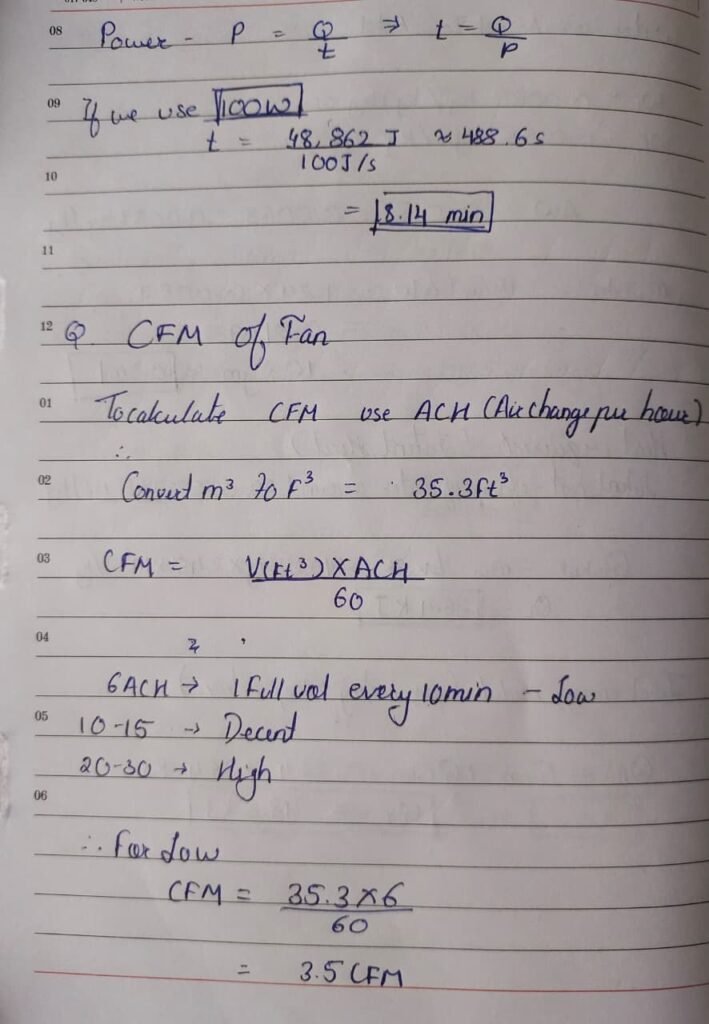

3. Air Circulation Fan (100 CFM)

Using your calculations based on:

- Required air changes per hour

- Chamber volume

- Flow stability

the ideal fan size came out to around 35–60 CFM for stable exchange, but we opted for a 100 CFM fan to ensure:

- Strong initial equalization

- Better mixing

- Future scalability

The fan will run at controlled duty cycles to maintain ideal airflow without drying the larvae.

23 Dec- 10 Jan/26

This week represented a critical learning phase where theoretical design assumptions were tested against real biological outcomes. After relocating the BSF chamber into a fully enclosed room with no direct exposure to sunlight, three separate pupae trays were introduced and monitored continuously. The intention behind moving the chamber indoors was to isolate it from external disturbances such as fluctuating daylight, wind, and ambient humidity.

However, after nearly three weeks of observation, pupal emergence remained extremely low, with only a handful of adult flies successfully hatching. This slow and limited emergence immediately indicated that one or more environmental parameters were outside the biological tolerance range required for successful metamorphosis.

Root Cause Identification: Temperature and Humidity Instability Detailed observation and periodic temperature measurements revealed a clear pattern: while daytime conditions were marginally acceptable, nighttime temperatures dropped significantly, especially during late night and early morning hours. These sustained low temperatures had a direct negative effect on pupal development.

Key biological insights identified during this phase:

BSF pupae require stable warmth throughout the metamorphic phase

Short-term cold exposure can delay emergence

Prolonged low temperatures can completely arrest development

Low temperature also reduces evaporation, indirectly lowering humidity

In addition to temperature drops, humidity levels inside the closed room decreased at night due to cooler air holding less moisture. The combined effect of low temperature and reduced relative humidity created a hostile microclimate for pupae, despite the enclosure being dark and isolated.

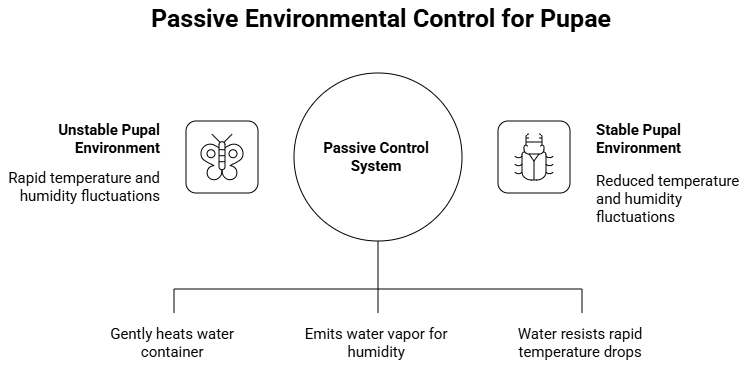

To counteract these issues, a revised environmental control approach was developed, focusing on simplicity, reliability, and passive stability rather than complex active systems.

Heating + Humidity Strategy Using Thermal Mass

The updated plan involves introducing a controlled electric heater inside the pupal enclosure, paired with an open water container placed in close proximity. The heater will gently heat the water, allowing partial boiling or sustained near-boiling conditions depending on ambient losses.

This design creates multiple stabilizing effects:

Sensible heating of surrounding air through convection

Latent heat release through water evaporation

Humidity increase as warm water continuously emits water vapor

Thermal buffering, where heated water resists rapid temperature drops at night

Instead of rapidly cycling heaters on and off, the warm water acts as a heat reservoir, smoothing out temperature fluctuations and preventing sharp drops during nighttime hours.

Advantages of This Approach Reduced reliance on active humidifiers

Lower risk of over-drying or oversaturation

Simple mechanical implementation

Easier maintenance and failure detection

More biologically natural microclimate

This setup is especially suited for pupae, which benefit more from environmental stability than rapid response control.

Building a Small Experimental Chamber for Better Observation

Alongside improving the main pupal setup, I also designed and built a smaller experimental chamber to study BSF behavior under more controlled conditions.

The chamber has overall dimensions of approximately 1 feet × 1 feet × 2 feet, and it is internally divided into two sections:

One 1 ft³ open, illuminated area

One 1 ft³ dark enclosure

The dark section was created using thick black cloth instead of solid walls. I specifically chose this material because it blocks light effectively while remaining breathable. This allows natural air movement through the fabric, supporting passive convection without trapping heat or moisture.

This design avoids stagnant air pockets and helps maintain a more even temperature and humidity distribution, while still giving the flies a properly dark resting area.

Integration with Egg Incubator and Controlled Lighting

For the initial phase, this small chamber will be placed inside an egg incubator. Using the incubator allows me to maintain a stable baseline temperature while I fine-tune the internal conditions of the chamber itself.

I am also introducing specialized BSF lights in the illuminated section. These lights will help simulate controlled daylight conditions, making it possible to observe adult fly activity, movement, and behavior in a regulated environment.

This setup will allow me to:

Monitor emergence and activity patterns

Observe how flies move between light and dark zones

Study mating and aggregation behavior

Correlate environmental conditions with fly response

Having both light and dark areas within the same controlled enclosure helps replicate natural habitat cues while still keeping the system measurable and repeatable.

Controlled Incubation Trial Setup

To improve consistency and repeatability in the Black Soldier Fly (BSF) rearing process, a controlled incubation trial has been initiated using an egg incubator. The primary objective is to minimize environmental fluctuations and study BSF development under stable, measurable conditions.

The incubator has been set to:

- Temperature: 28 °C

- Relative Humidity: ~70 %

These parameters fall within the acceptable range for BSF egg incubation and early larval development. Maintaining this environment allows better control over hatching time, larval survival, and early growth behavior.

Trial Duration and Scope

The trial will run for 45 days, covering multiple stages of the BSF lifecycle. This duration is sufficient to observe:

- Egg hatching response

- Early larval growth rate

- Transition towards later larval and pupal stages

Observations will focus on development speed, survival rate, and any visible stress indicators caused by temperature or humidity variation.

Lighting Intervention

A special-purpose light has been installed inside the chamber. The intent is not direct stimulation of eggs or early larvae but to prepare the system for later stages where light plays a role in adult activity and reproduction.

The lighting setup will remain consistent throughout the trial to assess whether a stable light environment influences:

- Overall development timing

- Adult emergence readiness in later stages

Any behavioral or developmental changes will be documented.

Observations and Monitoring

Key parameters being monitored during the trial:

- Stability of temperature and humidity

- Egg hatch duration

- Larval activity and aggregation behavior

- Moisture buildup or fungal growth

- System reliability over extended operation

Adjustments will be minimal and recorded to maintain experimental integrity.

Next Steps

At the end of the 45-day period, observations will be consolidated to evaluate whether a controlled incubator-based setup improves predictability and survival compared to open or semi-controlled systems. The results will inform further optimization of the BSF rearing setup and scaling strategies.